|

Famous

Players

Tigran Petrosian

Tigran

Petrosian (June 17, 1929 – August 13, 1984) was World

Champion from 1963 to 1969.

He is often known by the Russian

version of his name, Tigran

Vartanovich Petrosian (Russian:

Тигран Вартанович Петросян). He

was nicknamed "Iron Tigran" due

to his playing style because of

his almost impenetrable defence,

which emphasised safety above

all else. He was a Candidate for

the World Championship on eight

occasions (1953, 1956, 1959,

1962, 1971, 1974, 1977 and

1980). He won the world

championship in 1963 (against

Botvinnik), successfully

defended it in 1966 (against

Spassky), and lost it in 1969

(to Spassky). Thus he was the

defending World Champion or a

World Champion candidate in ten

consecutive three-year cycles.

He won the Soviet Championship

four times (1959, 1961, 1969,

and 1975). He was arguably the

hardest player to beat in the

history of chess.

Petrosian's first important result was a shared 1st-3rd

place at the 4th USSR Junior Championship, Leningrad 1945,

with 11/15; he tied with Y. Vasilchuk and A. Reshko. In the

6th Armenian Championship, Yerevan 1946, Petrosian won the

title with 9/10. But that same year at Leningrad for the

Candidates to Masters event, he could only score 6½/15 for a

shared 8th-11th place. In the 7th Georgian Championship,

Tbilisi 1946, Petrosian scored 12½/19, and was second among

Georgians; the winner Paul Keres (18/19) played hors

concours ("far ahead of the competition"), and conceded just

two draws, one of them to Petrosian. He failed badly at the

USSR Championship semi-final, Tbilisi 1946, with just 6/17,

for a shared 16th-17th place. Petrosian claimed the title in

the 5th USSR Junior Championship, Leningrad 1946, with an

unbeaten 14/15. In the 1947 Armenian Championship, Petrosian

shared 2nd-4th places, with 8½/11, behind Igor Bondarevsky,

who played hors concours. In the 1948 Championship of

Caucasian Republics, Petrosian came 2nd with 9/12, behind

winner Vladimir Makogonov. In the 8th Armenian Championship

of 1948, Petrosian shared the title on 12½/13 with Genrikh

Kasparian.

Despite

growing up and starting his chess career in Georgia,

Petrosian was regarded by his Soviet teammates as Armenian.

For example when Bobby Fischer said he intended to beat "all

the Russians" at the Bled 1961 tournament, Paul Keres told

him that there were no Russians in the tournament: Mikhail

Tal was a Latvian, Petrosian an Armenian, Efim Geller a

Ukrainian, and Keres himself was an Estonian. Western

publications described Petrosian as an Armenian.

|

|

|

Petrosian (seated right) plays Fischer during

the

USSR v Rest of the World match in 1970. |

|

A

significant step for Petrosian was moving to Moscow in 1949,

where he began to play and win many tournaments. Moscow,

along with Leningrad and Kiev, were the three major Soviet

chess cities. He won the 1951 tournament in Moscow, and

began to show steady progress. By 1952 Petrosian became a

Soviet and international Grandmaster in chess. Prior to

taking up chess full time though, Petrosian was a caretaker

and a road sweeper. In 1952, he married Rona Yakovlevna

Avinezar, a translator who was active in chess circles.

In the

1963 World Championship cycle, he won the Candidates

tournament at Curaçao in 1962, then in 1963 he defeated

Mikhail Botvinnik 12½–9½ to become World Chess Champion. His

patient, defensive style frustrated Botvinnik, who only

needed to make one risky move for Petrosian to punish him.

Petrosian is the only player to go through the Interzonal

and the Candidates process undefeated on the way to the

world championship match. Petrosian shared first place with

Paul Keres at the Piatigorsky Cup, Los Angeles 1963, his

first tournament after winning the championship.

Petrosian

defended his title in 1966 by defeating Boris Spassky

12½–11½. He was the first World Champion to win a title

match while champion since Alekhine beat Bogoljubov in 1934.

In 1968, he was granted a PhD from Yerevan State University

for his thesis, "Chess Logic". In 1969 Spassky got his

revenge, winning by 12½–10½ and taking the title.

He was the only player to win a game against Bobby Fischer

during the latter's 1971 Candidates matches, finally

bringing an end to Fischer's amazing streak of twenty

consecutive wins (seven to finish the 1970 Palma de Mallorca

Interzonal, six against Taimanov, six against Larsen, and

the first game in their match). Nevertheless Petrosian lost

the match.

Some of his late successes included victories at Lone Pine

1976 and in the 1979 Paul Keres Memorial tournament in

Tallinn (12/16 without a loss, ahead of Tal, Bronstein and

others), shared first place (with Portisch and Huebner) in

the Rio de Janeiro Interzonal the same year, and second

place in Tilburg in 1981, half a point behind the winner

Beliavsky. It was here that he played his last famous

victory, a miraculous escape against the young Garry

Kasparov.

Petrosian died of stomach cancer in 1984 in Moscow. He is

buried in Vagankovo Cemetery and in 1987 13th World Chess

Champion

Garry Kasparov unveiled a memorial in the cemetery at

Petrosian's grave which depicts the laurel wreath of world

champion and an image contained within a crown of the sun

shining above the twin peaks of Mount Ararat - the national

symbol of his native Armenia.

2100 Petrosian

games in

PGN

Vasily Smyslov

Vasily Vasiliyevich Smyslov

(Russian: Васи́лий Васильевич

Смысло́в) (March 24, 1921 -

March 27 2010) was World Chess

Champion from 1957 to 1958.

He was a Candidate for the World

Chess Championship on eight

occasions (1948, 1950, 1953,

1956, 1959, 1965, 1983, and

1985). Smyslov was twice Soviet

Champion (1949, 1955), and his

total of 17 Chess Olympiad

medals won is an all-time

record. In five European Team

Championships, Smyslov won ten

gold medals.

In 1938, at age 17, he won

the USSR Junior Championship. That same year, he tied for

1st-2nd place in the Moscow City Championship, with 12½/17.

However, Smyslov's first attempt at adult competition

outside his own city fell short; he placed 12th-13th in the

Leningrad-Moscow International tournament of 1939 with 8/17

in an exceptionally strong field. In the Moscow Championship

of 1939-40 Smyslov scored 9/13.

In his first Soviet final,

the 1940 USSR Championship (Moscow, URS-ch12), he performed

exceptionally well for 3rd place with 13/19, finishing ahead

of the reigning champion Mikhail Botvinnik. This tournament

was the strongest Soviet final up to that time, as it

included several players, such as Paul Keres and Vladas

Mikėnas, from countries annexed by the USSR, as part of the

Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939.

The Soviet Federation held

a further tournament of the top six from the 1940 event, and

this was called the 1941 Absolute Championship of the USSR,

one of the strongest tournaments ever organized. The format

saw each player meet his opponents four times. The players

were Botvinnik, Keres, Smyslov, Isaac Boleslavsky, Igor

Bondarevsky, and Andor Lilienthal. Smyslov scored 10/20 for

third place, behind Botvinnik and Keres. This proved that he

was of genuine world-class Grandmaster strength at age 20, a

very rare achievement at that time.

The Second World War

forced a halt to most international chess. But several

tournaments involving Soviet players only were still

organized. Smyslov won the 1942 Moscow Championship outright

with a powerful 12/15 and he emerged as champion from the

1944-45 Moscow Championship with 13/16.

As the war ended,

organized chess picked up again. But Smyslov's form hit a

serious slump in the immediate post-war period. In the 1945

USSR Championship at Moscow (URS-ch14), Smyslov was in the

middle of the very powerful field with 8.5/17; the winner

was Botvinnik, with Boleslavsky and the new star David

Bronstein occupying second and third places.

Smyslov played in the 1948

World Chess Championship tournament to determine who should

succeed the late Alexander Alekhine as champion, finishing

second behind Mikhail Botvinnik, with a score of 11/20. With

this second-place Smyslov entered the 1950 Budapest

Candidates' tournament. He scored 10/18 for third place,

behind Bronstein and Boleslavsky, who tied for first place.

He was awarded the International Grandmaster title in 1950

by FIDE on its inaugural list.

After winning the

Candidates Tournament in Zurich 1953, with 18/28, two points

ahead of Keres, Bronstein, and Samuel Reshevsky, Smyslov

played a match with Botvinnik for the title the following

year. Sited at Moscow, the match ended in a draw, after 24

games (seven wins each and ten draws), meaning that

Botvinnik retained his title.

Smyslov had again won the

Candidates' Tournament at Amsterdam in 1956, which led to

another world championship match against Botvinnik in 1957.

Assisted by trainers Vladimir Makogonov and Vladimir

Simagin, Smyslov won by the score 12.5-9.5. The following

year, Botvinnik exercised his right to a rematch, and won

the title back with a final score of 12.5-10.5. Smyslov

later said his health suffered during the return match, as

he came down with pneumonia, but he also acknowledged that

Botvinnik had prepared very thoroughly.

Smyslov didn't qualify for

another World Championship, but continued to play in World

Championship qualifying events. In 1959, he was a Candidate,

but finished fourth in the qualifying tournament held in

Yugoslavia, which was won by the rising superstar Mikhail

Tal. He missed out in 1962, but was back in 1964, following

a first-place tie at the Amsterdam Interzonal, with 17/23.

But he lost his first-round match to Efim Geller.

|

|

|

2006 |

|

In 1983, at the age of 62, he

went through to the Candidates'

Final (the match to determine

who plays the champion, in that

case Anatoly Karpov), losing 8.5

- 4.5 at Vilnius 1984 to Garry

Kasparov, who was ¼ his age, and

who went on to beat Karpov to

become world champion in 1985.

Smyslov won two Soviet

championships. He tied for first and second places in the

1949 Soviet Championship (URS-ch17) at Moscow, with David

Bronstein. At Venice 1950, he finished second with 12/15. He

tied for first place with Efim Geller at Moscow 1955 in the

URS-22ch, but lost the playoff match. He won at Mar del

Plata 1966.

Smyslov represented the

Soviet Union a total of nine times at chess Olympiads, from

1952 to 1972 inclusive, excepting only 1962 and 1966. He

contributed mightily to team gold medal wins on each

occasion he played, winning a total of eight individual

medals. His total of 17 Olympiad medals won, including team

and individual medals, is an all-time Olympiad record.

He was known for his

positional style, and, in particular, his precise handling

of the endgame, but many of his games featured spectacular

tactical shots as well. He made enormous contributions to

chess opening theory in many openings, including the English

Opening, Grunfeld Defence, and the Sicilian Defence.

Perhaps in tribute to his

probing intellect, Stanley Kubrick named a character after

him in his film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Smyslov was a fine

baritone singer, who only positively decided upon a chess

career after a failed audition with the Bolshoi Theatre in

1950. He once said, "I have always lived between chess

and music." On the occasion of a game against Botvinnik,

he sang to an audience of thousands. He occasionally gave

recitals during chess tournaments, often accompanied by

fellow Grandmaster and concert pianist Mark Taimanov.

Smyslov once wrote that he tried to achieve harmony on the

chess board, with each piece assisting the others (Smyslov's

Selected Games, by Vasily Smyslov, 1995, London, Everyman

Chess, introduction).

2749 Smyslov games in

PGN

Mikhail Botvinnik

Mikhail Moiseyevich Botvinnik

(Russian: Михаи́л Моисе́евич

Ботви́нник) (August 17 1911 –

May 5, 1995) was the first

world-class player to develop

within the Soviet Union, putting

him under political pressure but

also giving him considerable

influence within Soviet chess.

From time to time he was accused

of using that influence to his

own advantage.

He also played a major role in

the organization of chess,

making a significant

contribution to the design of

the World Chess Championship

system after World War II and

becoming a leading member of the

coaching system that enabled the

Soviet Union to dominate

top-class chess during that

time. One of his famous pupils

was Garry Kasparov.

He first

came to the notice of the chess world at the age of 14, when

he defeated the world champion, José Raúl Capablanca, in a

simultaneous exhibition. He had started playing only two

years earlier. His progress was fairly rapid, mostly under

the training of Soviet Master and coach Abram Model, in

Leningrad. He qualified for his first USSR Championship

final stage in 1927 as the youngest player ever at that

time, tied for 5th place and won the title of National

Master.

He won the Leningrad Masters' tournament in 1930 with 6½/8.

He followed this up the next year by winning the

Championship of Leningrad by 2½

points over former Soviet champion Peter Romanovsky.

At the

age of 20 Botvinnik won his first Soviet Championship at

Moscow 1931, with 13½/17.

In the spring of that year, he graduated in Electrical

Engineering from the Leningrad Polytechnical Institute, and

stayed on there as a post-graduate student. In 1933, he

repeated his Soviet Championship win, this time in his home

city of Leningrad, with 14/19.

Botvinnik

would go on to win a total of six Soviet Championships,

adding further titles in 1939, 1944, 1945, and 1952 (in 1952

he tied with Mark Taimanov and won the play-off match). This

is tied for the most ever with Mikhail Tal. His 1945 win was

with an utterly dominant score of 16/18, one of the top

tournament performances of all time.

The year

1938 brought the famous AVRO tournament in the Netherlands,

which featured the world's top eight players, and may have

been the strongest tournament yet seen – some chess

historians believe that it is the strongest ever held. The

winner was supposed to get a title match with the World

Champion Alexander Alekhine. Botvinnik placed third (behind

Paul Keres and Reuben Fine. Alekhine accepted a challenge

from Botvinnik, but the arrival of World War II prevented a

World Championship match.

In 1941, Botvinnik won a match-tournament designating him

the title of "Absolute Champion of the U.S.S.R". Botvinnik

defeated Paul Keres and future world champion Vasily

Smyslov, amongst other strong Soviet grandmasters such as

Isaac Boleslavsky, Igor Bondarevsky, and Andor Lilienthal,

to win the title. Chess historians debate whether this

constitutes an official Soviet Championship title.

When the Second World War ended, Botvinnik won the first

really strong post-war tournament, at Groningen 1946, with

14½/19, half a point ahead of former World Champion Max

Euwe; this was Botvinnik's first non-shared first place in a

tournament outside the Soviet Union, and Smyslov was a

strong third. Botvinnik also won the very strong Mikhail

Chigorin Memorial tournament held at Moscow 1947.

Botvinnik strongly influenced the design of the system which

would be used for World Championship competition from 1948

to 1963. Viktor

Baturinsky

wrote, in his introduction to Botvinnik's own book

Botvinnik's Best Games 1947–1970 (page 2), "Now came

Botvinnik's turn to defend his title in accordance with the

new qualifying system which he himself had outlined in

1946."

|

|

|

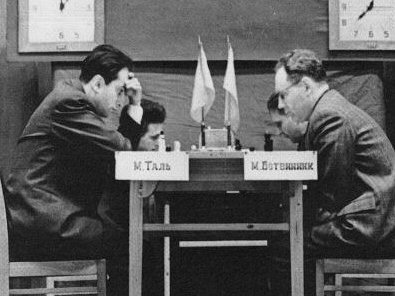

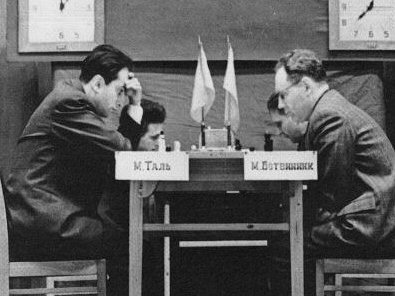

Tal v

Botvinnik, Moscow 1960 |

|

Botvinnik

then held the title, with two brief interruptions, for the

next fifteen years, during which he played seven world

championship matches. In 1951, he drew with David Bronstein

over 24 games in Moscow, +5 =14 -5, keeping the world title;

but it was

a struggle for Botvinnik, who won the second-last game and

drew the last in order to tie the match. In 1954, he drew

with Vasily Smyslov over 24 games at Moscow, +7 =10 -7,

again keeping the title. In 1957 he lost to Smyslov by 9½–12½

in Moscow, but the rules allowed him a rematch without

having to go through the Candidates' Tournament, and in 1958

he won the rematch in Moscow; Smyslov said his health was

poor during the return match.

In 1960

Botvinnik was convincingly beaten by the 23-year old Mikhail

Tal, by 8½-12½ at Moscow; but again he exercised his right

to a rematch in 1961, and won by 13–8 in Moscow.

Commentators agreed that Tal's play was weaker in the

rematch, probably due to his health, but also that

Botvinnik's play was better than in the 1960 match, largely

due to thorough preparation; and Botvinnik changed his

style, avoiding the tactical complications in which Tal

excelled and aiming for endgames, where Tal's technique was

not outstanding. Finally, in 1963, he lost the title to

Tigran Petrosian, by 9½-12½ in Moscow. FIDE had by then

altered the rules, and he was not allowed a rematch. The

rematch rule was nicknamed the 'Botvinnik rule', because he

twice benefited from it.

Botvinnik

gained a doctorate in engineering in 1951. As an electrical

engineer, he was one of the very few famous chess players

who achieved distinction in another career while playing

top-class competitive chess.

Botvinnik

won the 1952 Soviet Championship (tied with Taimanov in the

tournament, won the play-off match). He included several

wins from that tournament over the 1952 Soviet team members

in his book Botvinnik's Best Games 1947–1970, writing "these

games had a definite significance for me". In 1956 he tied

for first place with Smyslov in the 1956 Alexander Alekhine

Memorial in Moscow.

Botvinnik

was selected for the Soviet Olympiad team from 1954 to 1964

inclusively, and helped his team to gold medal finishes each

of those six times. At Amsterdam 1954 he was on board one

and won the gold medal with 8⅓/11. Then at home for

Moscow 1956, he was again board one, and scored 9⅓/13 for

the bronze medal. For Munich 1958, he

scored 9/12 for the silver medal on board one. At Leipzig

1960, he played board two behind Mikhail Tal, having lost

his title to Tal earlier that year; But he won the board two

gold medal with 10⅓/13. He was back on board one for

Varna 1962, scored 8/12, but

failed to win a medal for the only time at an Olympiad. His

final Olympiad was Tel Aviv 1964, where he won the bronze

with 9/12, playing board 2 as he had lost his title to

Petrosian. Overall, in six Olympiads, he scored 54½/73 for

an outstanding 74.0 per cent.

Botvinnik

also played twice for the USSR in the European Team

Championship. At Oberhausen 1961, he scored 6/9 for the gold

medal on board one. But at Hamburg 1965, he struggled on

board two with only 3½/8. Both times the Soviet Union won

the team gold medals. Botvinnik played one of the final

events of his career at the Russia (USSR) vs Rest of the

World match in Belgrade 1970, scoring 2½/4 against Milan

Matulovic, as the USSR narrowly triumphed.

He retired from competitive play in 1970 aged 59, preferring

instead to occupy himself with the development of computer

chess programs and to assist with the training of younger

Soviet players, earning him the nickname of "Patriarch of

the Soviet Chess School".

Botvinnik sent an effusive telegram of thanks to Stalin

after his victory at the great tournament in Nottingham in

1936. Many years later he said that it had been written in

Moscow and that KGB agents told him to sign it.

Since Keres lost his first four games against Botvinnik in

the 1948 World Championship tournament, suspicions are

sometimes raised that Keres was forced to "throw" games to

allow Botvinnik to win the Championship. Chess historian

Taylor Kingston investigated all the available evidence and

arguments, and concluded that: Soviet chess officials gave

Keres strong hints that he should not hinder Botvinnik's

attempt to win the World Championship; Botvinnik only

discovered this about half-way through the tournament and

protested so strongly that he angered Soviet officials.

Bronstein insinuated that Soviet officials pressured him to

lose in the 1951 world championship match so that Botvinnik

would keep the title. But comments by Botvinnik's second

Salo Flohr and Botvinnik's own annotations about the

critical 23rd game indicate that Botvinnik knew of no such

plot.

While there is no doubt that Botvinnik sincerely believed in

Communism, he by no means followed the party line

submissively. For example in 1948 he publicly supported the

founding of the state of Israel – although he later made a

distinction between the "hard-working Jews and Arabs living

in this wonderful country" and "the Arab petrol tycoons and

the wealthy American Jews". In 1954 he wrote an article

about inciting socialist revolution in western countries,

aiming to spread Communism without a third world war. And in

1960 Botvinnik wrote a letter to the Soviet Government

proposing economic reforms that were contrary to party

policy.

In 1976 Soviet grandmasters were asked to sign a letter

condemning Viktor Korchnoi as a "traitor" after Korchnoi

defected. Botvinnik evaded this "request" by saying that he

wanted to write his own letter denouncing Korchnoi. But by

this time his importance had waned and officials would not

give him this "privilege", so Botvinnik's name did not

appear on the group letter – an outcome Botvinnik may have

foreseen. David Bronstein and Boris Spassky openly refused

to sign the letter.

980 Botvinnik games in

PGN.

Max Euwe

Machgielis (Max) Euwe (May 20,

1901 – November 26, 1981) was a

Dutch chess Grandmaster,

Mathematician, and author. He

was the fifth player to become

World Chess Champion

(1935–1937).

Euwe was

born in Watergraafsmeer, near Amsterdam. He studied

mathematics at the University of Amsterdam, earning his

doctorate in 1926, and taught mathematics, first in

Rotterdam, and later at a girls' Lyceum in Amsterdam. He

published a mathematical analysis of the game of chess from

an intuitionistic point of view, in which he showed, using

the Thue-Morse sequence, that the then current official

rules did not exclude the possibility of infinite games.

Euwe won

every Dutch chess championship that he participated in from

1921 until 1952, and additionally won the title in 1955 -

his 12 titles are still a record. The only other winners

during this period were Salo Landau in 1936, when Euwe, then

world champion, did not compete, and Jan Hein Donner in

1954. He became the world amateur chess champion in 1928, at

The Hague, with a score of 12/15.

At Zürich

1934, Euwe finished second, behind only World Champion

Alexander Alekhine, and he defeated Alekhine in their game.

Alekhine was in an eight-year stretch, from 1927-35, where

he lost only six games in tournament play.

On

December 15, 1935 after 30 games played in 13 different

cities around The Netherlands over a period of 80 days, Euwe

defeated Alekhine, by 15½-14½, becoming the fifth World

Chess Champion. Alekhine quickly went two games ahead, but

from game 13 onwards Euwe won twice as many games as

Alekhine. His title gave a huge boost to chess in The

Netherlands. This was also the first world championship

match in which the players had seconds to help them with

analysis during adjournments.

Euwe's

performances in the great tournaments of Nottingham 1936 and

the 1938 AVRO tournament indicate he was a worthy champion,

even if he was not as dominant as the earlier champions but

lost the title to Alekhine in a rematch in 1937, also played

in The Netherlands, by a rather one-sided margin of 15½-9½.

He played

a match with Paul Keres in The Netherlands in 1939-40,

losing 6½-7½.

After

Alekhine's death in 1946, Euwe was considered by some to

have a moral right to the position of world champion, based

at least partially on his clear second place finish in the

great tournament at Groningen in 1946, behind Mikhail

Botvinnik. But Euwe consented to participate in a

five-player tournament to select the new champion, the World

Chess Championship 1948. However at 47, Euwe was

significantly older than the other players, and well past

his best, and he finished last.

He played

for The Netherlands in a total of seven chess Olympiads,

from 1927 to 1962, a 35-year-span, always on first board. He

scored 10½/15 at London 1927, 9½/13 at Stockholm 1937 for a

bronze medal, 8/12 at Dubrovnik 1950, 7½/13 at Amsterdam

1954, 8½/11 at Munich 1958 for a silver medal at age 57,

6½/16 at Leipzig 1960, and finally 4/7 at Varna 1962. His

aggregate was 54½/87 for 62.6 per cent.

From 1970

(when he was 69 years old) until 1978, he was president of

the FIDE. As president Euwe usually did what he considered

morally right rather than what was politically expedient. On

several occasions this brought him into conflict with the

Soviet Chess Federation, which thought it had the right to

call the shots because it contributed a very large share of

FIDE's budget.

Euwe lost

some of the battles with the Soviets. For example in 1973 he

accepted the Soviets' demand that Bent Larsen and Robert

Hübner, the two strongest non-Soviet contenders (Fischer was

now champion), should play in the Leningrad Interzonal

tournament rather than the weaker one in Petropolis.

Unsurprisingly Larsen and Hübner were eliminated from the

competition for the World Championship because Korchnoi and

Karpov took the first 2 places at Leningrad. Some

commentators have also questioned whether Euwe did as much

as he could have to prevent Fischer from forfeiting his

world title in 1975.

He died in

1981, age 80, of a heart attack. Revered around the chess

world for his many contributions, he had

travelled extensively while FIDE President, bringing many new

members into the organization.

1400 Euwe

games in PGN.

Alexander Alekhine

Alexander Alekhine (1892 - 1946) was born in Moscow. He was

the son of wealthy parents. At the age of eleven his mother

taught him to play chess and he soon developed a great

passion for the game.

His first chess achievement was when, at the age of

seventeen, he won the All-Russian Amateur Tournament in St.

Petersburg (+12 -2 =2). He was awarded a national master

title for this performance. The tournament was held

concurrently with the more famous international event won by

Emanuel Lasker and

Akiba

Rubinstein. Meanwhile, in the United States, later

that year a 23 year old Cuban

called

José

Raúl Capablanca shocked American chess players by

easily beating

Frank

Marshall in a match.

In 1914, after Alekhine finished

3rd behind Lasker and Capablanca

in a tournament in St

Petersburg, Tsar Nicholas II

named him as one of the five

original grandmasters. Alekhine

also served in World War 1, and

was wounded. He then lived in

many countries, speaking

Russian, French, German, and

English.

Following the Russian Revolution, in 1919 he was suspected

of espionage, arrested and imprisoned in Odessa, though he

was eventually freed. He won the 1st USSR Championship in

1920. In 1921 Alekhine left Soviet Russia never to return,

moving to France, where four years later he became a French

citizen and entered the Sorbonne Faculty of Law. Although

his thesis on the Chinese prison system went uncompleted, he

nevertheless claimed the title of "Dr Alekhine". From 1921

to 1927, Alekhine amassed an excellent tournament record,

winning or sharing 12 out of 20 first prizes in the

tournaments he played.

In 1927 he won the World chess championship

against Capablanca, to the surprise of almost all the

chess world. After that, if Capablanca was invited to

tournaments, Alekhine would insist on greater money;

otherwise he would refuse to play. Although Capablanca was

clearly the leading challenger, Alekhine carefully avoided

granting a rematch, although a right to a rematch was part

of the agreement. Instead, he played matches with Efim

Bogoljubow in 1929 and 1934, winning easily both times.

After defeating Capablanca, Alekhine dominated chess for

some time. He lost only 7 out of 238 games in tournament

play from 1927 - 1935.

In 1935 he carelessly lost the title to Max Euwe. The loss

is largely attributed to Alekhine's alcoholism and lack of

preparation. At the great Nottingham tournament in 1936 he

also lost his game against Capablanca who went on to win the

tournament (tied with Mikhail Botvinnik). Alekhine

gave up alcohol and regained the title from Euwe in

1937

by a large margin. He played no more title matches, so he

held the title until his death. While planning for a World

championship match against Botvinnik, he died in his hotel

room in

Estoril,

Portugal. His death, the circumstances of which are

still disputed, is thought to have been caused either by his

choking on a piece of meat or by a heart attack. His burial

was sponsored by

FIDE,

and the remains were transferred to the Cimetière du

Montparnasse,

Paris,

France in 1956.

2079

Alekhine games in

PGN.

Richard

Réti

Richard Réti (28 May 1889,

Pezinok

(now Slovakia) - 6 June 1929, Prague) was a Czechoslovakian

chess player, although he was born in Pezinok which at the time was in

Hungary. He studied mathematics and physics at Vienna, where he found

the time to hone his chess skills, and shortly before the First World

War became a chess professional.

He earned his living partly by

writing chess columns and giving displays; in particular he was

expert at blindfold chess. He was one of the top players in the world

during the 1910s and 1920s and began his career as a fiercely

combinative classical player, favouring openings such as the King's

Gambit (1. e4 e5 2. f4).

However, after the end of the First World War, his playing

style underwent a radical change, and he became one of the

principal proponents of hypermoderism, along with Aron

Nimzowitsch and others. Indeed, with the notable exception

of Nimzowitsch's acclaimed book My System, he is considered

to be the movement's foremost literary contributor. The Réti

Opening (1. Nf3 d5 2. c4), with which he famously defeated

the world champion José Raúl Capablanca in New York in 1924

- Capablanca's first defeat for eight years and the first

since becoming World Champion - is named after him. He was

also a notable composer of endgame studies creating simple

and natural-looking positions that would appeal to the

majority of players. In 1925 Réti set the world record for

blindfold chess with twenty-nine games played

simultaneously. He won twenty-one of these, drew six and

only lost two! His writings have also become 'classics' in

the chess world. 'New Ideas in Chess' from 1922 and 'Masters

of the Chessboard' from 1930 published after his death, are

still studied today.

As a cultured and educated man, Réti regarded chess as an

art, and his books, in the eyes of many chess enthusiasts,

reveal the hand of an artist. However, lacking adequate sources Réti was

unaware that some positional ideas were known earlier than

he supposed, and he failed to mention the contributions made

by Staunton, Paulsen and Chigorin.

He died on June 6, 1929 in Prague of scarlet fever aged just

40.

698 Réti

games in PGN.

José Raúl Capablanca

José Raúl Capablanca (November 19, 1888 - March 8, 1942).

Referred to by many chess historians as the Mozart

of chess, Capablanca was a chess prodigy whose brilliance

was

noted at an early age. In 1901, at the age of 12, he

defeated Cuban national champion Juan Corzo by the score of

4 wins, 3 losses, and 6 draws.

In 1909, at the age of 20,

Capablanca won a match against

US champion Frank Marshall. In

1911, Capablanca challenged

Emanuel Lasker for the world

championship. Lasker accepted

his challenge but proposed

seventeen conditions for the

match. Capablanca disapproved of

some of the conditions and the

match did not take place.

In 1914 he

beat Bernstein in Moscow in a game listed in many

anthologies as a brilliancy for the winning move ...Qb2!!

and for the new strategy with hanging pawns, and defeated

Nimzowitsch in an elegant opposite-coloured bishop endgame.

At the great 1914 tournament in St. Petersburg, with most of

the world's leading players, Capablanca met Lasker across

the chessboard for the first time in normal tournament play

(Capablanca had won a knock-out lightning chess final game

in 1906, leading to a famous joint endgame composition).

Capablanca took the large lead of one and a half points in

the preliminary rounds, and made Lasker fight hard to draw.

He again won the first brilliancy prize against Bernstein

and had some highly regarded wins against David Janowsky,

Nimzowitsch and Alekhine. Capablanca finished second to

Lasker with a score of 13 points to Lasker's 13½, but ahead

of third-placed Alexander Alekhine.

In 1920,

Lasker saw that Capablanca was becoming too strong, and

resigned the title to him, saying, "You have earned the

title not by the formality of a challenge, but by your

brilliant mastery." The new world champion dominated the

field at London, 1922. There were an increasing number of

strong chess players and it was felt that the world champion

should not be able to evade challenges to his title, as had

been done in the past. Capablanca was second behind Lasker

in New York 1924, and again ahead of third-placed Alekhine.

He was third behind Efim Bogoljubov and Lasker in Moscow

1925. But he dominated the 6-player match tournament in New

York 1927, not losing a game and 2½ points ahead of

Alekhine.

Capablanca

had overwhelming success in New York 1927, a quadruple-round

robin with six of the world's top players. He was undefeated

and 2½ points ahead of the second-placed Alekhine.

Capablanca also defeated Alekhine in their first game, won

the first brilliancy prize against Rudolf Spielmann and won

fine two games against Aron Nimzowitsch.

This made

him the prohibitive favourite for his match with Alekhine,

who had never defeated him, later that year. However, the

challenger had prepared well, and played with patience and

solidity, and the marathon match proved to be Capablanca's

undoing. Capablanca lost the first game in very lacklustre

fashion, then took a narrow lead by winning games 3 and 7 -

attacking games more in the style of Alekhine - but then

lost games 11 and 12. He tried to get Alekhine to annul the

match when both players were locked in a series of draws.

Alekhine refused, and eventually prevailed +6 -3 =25.

In 1934,

Capablanca resumed serious play. He had begun dating Olga

Chagodayev, whom he married in 1938, and she inspired him to

play again. In 1935, Alekhine, plagued by problems with

alcohol, lost his title to Euwe. Capablanca had renewed

hopes of regaining his title, and he won Moscow 1936, ahead

of Botvinnik and Lasker. Then he tied with Botvinnik in the

super-tournament of Nottingham 1936, ahead of Euwe, Lasker,

Alekhine, and the leading young players Reuben Fine, Samuel

Reshevsky (avenging a defeat here) and Salo Flohr.

This was Capablanca's first game with Alekhine since their

great match, and the Cuban did not miss his chance to avenge

that defeat. He had the worse position, but caught Alekhine

in such a deep trap, allowing him to win the exchange, that

none of the other players could work out where Alekhine went

wrong, except Lasker who immediately saw the mistake.

Capablanca's health took a turn for the worse. He suffered a

small stroke during the AVRO tournament of 1938, and had the

worst result of his career, 7th out of 8. But even at this

stage of his career he was capable of producing strong

results. In the 1939 Chess Olympiad in Buenos Aires, he made

the best score on top board for Cuba, ahead of Alekhine and

Paul Keres.

On 7 March 1942, he was happily kibitzing a skittles game at

Manhattan Chess Club in New York when he collapsed from a

stroke. He was taken to Mount Sinai hospital, where he died

the next morning.

1195

Capablanca games in

PGN.

Aron

Nimzowitsch

Aron

Nimzowitsch (November 9, 1886, Riga - March 16, 1935,

Denmark) was a grandmaster

of considerable strength and a very influential chess

writer. He was the foremost figure amongst the hypermoderns.

Nimzowitsch came from a wealthy

Jewish family and learned chess

from his father. He travelled to

Germany in 1904 to study

philosophy, but began a career

as a professional chess player

that same year. After tumultuous

years during and after World War

I, Nimzowitsch moved to

Copenhagen in 1922 (some sources

say 1920) and lived there until

his death. He is buried in

Bispebjerg Cemetery in

Copenhagen.

At the

height of his career, Nimzowitsch was the third best player

in the world, immediately behind Alekhine and Capablanca.

His most notable successes were first place finishes at

Copenhagen 1928, the Carlsbad tournaments of 1929 and second

place behind Alekhine at San Remo in 1930. Nimzowitsch never

developed a knack for match play though; his best match

success was a draw with Alekhine (though this match was only

three games long and was in 1914, 13 years before Alekhine

became world champion). Although Nimzowitsch did not win a

single game against Capablanca, he fared better against

Alekhine.

He wrote

three books on chess strategy: Mein System (My System)

(1925), Die Praxis meines System (The Practice of my System)

(commonly known as Chess Praxis), and Die Blockade (The

Blockade). The last of these is hard to find in English,

however, and much that is in it is covered again in Mein

System. It is said that 99 out of 100 chess masters have

read Mein System; consequently, most consider My System to

be Nimzowitsch's greatest contribution to chess. It sets out

Nimzowitsch's most important ideas while his second most

influential work, Chess Praxis, elaborates upon these ideas,

adds a few new ones, and has immense value as a stimulating

collection of Nimzowitsch's own games even when these games

are more entertaining than instructive.

Nimzowitsch's chess theories flew in the face of

pre-existing convention. While there were those like

Alekhine, Lasker, and even Capablanca who did not live by

Tarrasch's rigid teachings, the acceptance of Tarrasch's

ideas, all simplifications of the more profound Steinitz,

was nearly universal. That the centre had to be controlled

by pawns and that development had to happen in support of

this control — the core ideas of Tarrasch's chess

philosophy—were things every beginner thought to be

irrefutable laws of nature like gravity.

Nimzowitsch shattered these assumptions. He discovered such

concepts as overprotection (the least important of his ideas

from a modern standpoint though still interesting and

sometimes applicable), control of the center by pieces

instead of pawns, blockade, prophylaxis — playing to prevent

the opponent's plans — and the fianchetto (in the case of

the fianchetto, one could argue that it was a rediscovery,

but Nimzowitsch certainly refined its use). He also

formalised strategies using open files, outposts and

invasion of the seventh rank, all of which are widely

accepted today.

Many chess

openings and variations are named after him, the most famous

being the Nimzo-Indian Defence (1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4)

and the less often played Nimzowitsch Defence (1.e4 Nc6).

Both of these exemplify Nimzowitsch's ideas about

controlling the center with pieces instead of pawns. He was

also vital in the development of two French Defense systems,

the Winawer Variation (in some places called the Nimzowitsch

Variation; its moves are 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 Bb4) and

the Advance Variation (1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. e5).

There are

numerous entertaining anecdotes regarding Nimzowitch - some

more savoury than others. For example, he once missed the

first prize by losing to Sämisch; immediately upon learning

this, Nimzowitsch got up on a table and shouted, “Why must I

lose to this idiot?”

556 Nimzowitsch

games in

PGN.

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Harry Nelson Pillsbury (December 5, 1872 - June 17, 1906)

was United States Chess Champion

from 1897 until his death in 1906. Pillsbury was born in

Somerville, Massachusetts, moved to New York City in 1894

and then again to Philadelphia in 1898.

By 1890, having only played

chess for two years he beat

noted chess expert H. N.

Stone. In April 1892, Pillsbury

played a match against World

Champion Wilhelm Steinitz,

(giving Pillsbury a pawn

advantage). Pillsbury won 2 - 1.

His rise was meteoric, and there

was soon no one to challenge him

in the New York chess scene.

The Brooklyn chess club sponsored his journey to Europe to

play in the Hastings 1895 chess tournament, in which all the

greatest players of the time participated. The 22-year-old

Pillsbury became a celebrity in the United States and abroad

by winning the tournament, finishing ahead of reigning world

champion Lasker and former world champion Steinitz and his

recent challenger

Mikhail Chigorin who was second. The dynamic style that

Pillsbury exhibited during the tournament also helped to

popularize the Queen's Gambit during the 1890s, including a

famous win over the powerful Siegbert Tarrasch in Hastings

1895.

His next big tournament was in St. Petersburg the same year,

where he appears to have contracted syphilis prior to the

start of the event. Although he was in the lead after the

first half of the tournament, he was affected by severe

headaches in the second, and lost no less than six games,

ultimately finishing third.

Pillsbury had an even record against Lasker (+5-5=4). He

even beat Lasker with black pieces at St Petersburg in 1895

and at Augsburg in 1900. Pillsbury also had an even score

against Steinitz (+5-5=3) and Tarrasch (+5-5=2),

but a slight minus against Chigorin (+7-8=6) and

surprisingly against Joseph Henry Blackburne (+3-5=4), while

he beat David Janowski (+6-4=2) and Geza Maroczy (+4-3=7)

and crushed Carl Schlechter (+8-2=9).

|

|

|

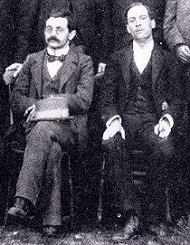

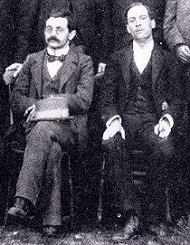

Lasker with Pillsbury,

Hastings 1895 |

|

Pillsbury was a very strong blindfold chess player, and

could play checkers and chess simultaneously while playing a

hand of whist, and reciting a list of long words. His

maximum was 22 simultaneous blindfold games at Moscow 1902.

However, his greatest feat was 21 simultaneous games

against

the players in the Hannover Hauptturnier of 1902—the winner

of the Hauptturnier would be recognized as a master, yet

Pillsbury scored +3-7=11. As a teenager, Edward Lasker

played Pillsbury in a blindfold exhibition in Breslau,

against the wishes of his mother, and recalled in ‘Chess

Secrets I learned from the Masters’,

But it soon became evident that I would have lost my game

even if I had been in the calmest of moods. Pillsbury gave a

marvellous performance, winning 13 of the 16 blindfold

games, drawing two, and losing only one. He played strong

chess and made no mistakes [presumably in recalling the

position]. The picture of Pillsbury sitting calmly in an

armchair, with his back to the players, smoking one cigar

after another, and replying to his opponents' moves after

brief consideration in a clear, unhesitating manner, came

back to my mind 30 years later, when I refereed Alekhine's

world record performance at the Chicago World's Fair, where

he played 32 blindfold games simultaneously. It was quite an

astounding demonstration, but Alekhine made quite a number

of mistakes, and his performance did not impress me half as

much as Pillsbury's in Breslau.

Poor health would prevent him from realizing his full

potential throughout the rest of his life. In spite of this,

Pillsbury beat American champion Jackson Showalter in 1897

to win the U.S. Chess Championship, a title he held

until he succumbed to syphilis in 1906. The stigma

surrounding the disease makes it unlikely that he sought

medical treatment. Some said that Pillsbury ruined his

health by all his blindfold displays, but those critics were

evidently unaware of the fatal organic illness.

Along with Paul Morphy and Bobby Fischer, Pillsbury ranks as

one of the USA's greatest-ever chess players. Unfortunately,

like the former, Pillsbury too had a short career.

425 Pillsbury games in

PGN.

Emanuel Lasker

Emanuel Lasker (December 24, 1868 - January

11, 1941) was a German chess player and

mathematician,

born at Berlinchen in Brandenburg (now Barlinek in Poland).

In 1894 he became the second

World Chess Champion by

defeating Steinitz

with 10 wins, 4 draws and 5

losses. He maintained this title

for 27 years, the longest

unbroken tenure of any

officially recognized World

Champion of chess. His great

tournament wins include London

(1899), St Petersburg (1896 and

1914), New York (1924).

In 1921, he lost the title to Capablanca. He had already

offered to resign to him a year before, but Capablanca

wanted to beat Lasker in a match.

In 1933, the Jewish Lasker and his wife Martha Kohn had to

leave Germany because of the Nazis. They went to England,

and, after a subsequent short stay in

the USSR, they settled in New York.

Lasker is noted for his "psychological" method of play in

which he considered the subjective qualities of his opponent

in addition to the objective requirements of his position on

the board. Richard Reti even speculated that Lasker would

sometimes knowingly choose inferior moves if he knew they

would make his opponent uncomfortable, although Lasker

himself denied this. But, for example, in one famous game

against Capablanca (St. Petersburg 1914) which he needed to

win at all costs, Lasker chose an opening that is considered

to be relatively harmless -- but only if the opponent is

prepared to mix things up in his own turn. Capablanca,

inclined by the tournament situation to play it safe, failed

to take active measures and so justified Lasker's strategy.

Lasker won the game.

One of Lasker's most famous games is Lasker - Bauer,

Amsterdam, 1889, in which he sacrificed both bishops in a

maneuver later repeated in a number of games. Some opening

variations are named after him, for example Lasker's Defense

(1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Bg5 Be7 5.e3 O-O 6.Nf3 h6 7.Bh4

Ne4) to the Queen's Gambit. In 1895, he introduced a line

that effectively ended the popular Evans Gambit in

tournament play (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.b4 Bxb4 5.c3

Ba5 6.d4 d6 7.0-0 Bb6 8.dxe5 dxe5 9.Qxd8+ Nxd8 10.Nxe5 Be6).

Lasker's line curbs White's aggressive intentions, and

according to Reuben Fine, the resulting simplified position

"is psychologically depressing for the gambit player."

Lasker was also a distinguished mathematician. He performed

his doctoral studies at Erlangen from 1900 to 1902 under

David Hilbert. His doctoral thesis, Über Reihen auf der

Convergenzgrenze, was published in Philosophical

Transactions in 1901.

Lasker introduced the concept of a primary ideal, which

extends the notion of a power of a prime number to algebraic

geometry. He is most

famous for his 1905 paper Zur Theorie der Moduln und Ideale,

which appeared in Mathematische Annalen. In this paper, he

established what is now known as the Lasker-Noether theorem

for the special case of ideals in polynomial rings.

He was also a philosopher, and a good friend of Albert

Einstein. Later in life he became an ardent humanitarian,

and wrote passionately about the need for inspiring and

structured education for the stabilization and security of

mankind. He also took up bridge and became a master at it,

in addition to studying Go.

He invented Lasca, a draughts-like game, where instead of

removing captured pieces from the board, they are stacked

underneath the capturer.

The poet Else Lasker-Schüler was his sister-in-law. He was

also related to the chess-player Edward Lasker.

1085

Lasker games in

PGN.

Siegbert Tarrasch

Siegbert Tarrasch (March 5, 1862 - February 17, 1934) was

one of the strongest chess players of the late 19th century

and early 20th century. Tarrasch was Jewish, and a patriotic

German

who lost a son in World War I, but lived to suffer under the

early stages of Nazism.

Tarrasch was a medical doctor by

profession who also may have been

the best player in the world in

the early 1890s. He scored

heavily against the aging

Steinitz in tournaments,

(+3-0=1), but refused an

opportunity to challenge for the

world title because of the

demands of his medical practice.

Soon afterwards, Tarrasch drew a

hard-fought match against his

challenger Mikhail Chigorin in

1893 (+9-9=4). Tarrasch also won

four major tournaments in

succession: Breslau 1889,

Manchester 1890, Dresden 1892

and Leipzig 1894.

However, after Emanuel Lasker became world chess champion in

1894, Tarrasch could not match him. Thereafter Tarrasch

always played the second fiddle. When Lasker finally agreed

to a title match in 1908, he beat Tarrasch convincingly

+8-3=5. However, Tarrasch was still very

powerful during Lasker's reign, demolishing Frank Marshall

in a match in 1905 (+8-1=8), and becoming one of the five

original grandmasters by becoming one of the five finalists

at the very strong St. Petersburg tournament of 1914. This

was probably his swan song, because his chess career was not

very successful after this, although he still played some

highly regarded games. Tarrasch was a well-known chess

writer, and was called Praeceptor Germaniae

meaning "Teacher of Germany". He wrote several books,

including Die moderne Schachpartie and Three

hundred chess games. But until recently, his books had

not been translated into English although his ideas became

famous.

He took Wilhelm Steinitz's ideas (control of the centre,

bishop pair, space advantage) to a higher level of

refinement. He emphasized piece mobility much more than

Steinitz did, and disliked cramped positions, saying that

they "had the germ of defeat". Tarrasch stated what

is known as the Tarrasch rule that rooks should be placed

behind passed pawns — either yours or your opponent's. A

number of chess openings are named after Tarrasch, with the

most notable being: The Tarrasch Defense, Tarrasch's

favorite line against the Queen's Gambit. The Tarrasch

Variation of the French Defense (3.Nd2), which Tarrasch

considered refuted by 3...c5.

772

Tarrasch games in

PGN.

Mikhail

Chigorin

Mikhail Chigorin (12 November

1850 - 25 January 1908) was a leading Russian chess player

and the first grandmaster from Russia. He served as a major

source of inspiration

for the "Soviet school of

chess," which dominated the chess world in the latter part

of the 20th century. He played two matches against Wilhelm

Steinitz for the World Chess Championship; the first in 1889

he lost 10½–6½;

the second in 1892 he lost 12½–10½.

His overall record against Steinitz was respectable:

+24-27=8.

He drew a match with Siegbert Tarrasch in Saint Petersburg

in 1893 (+9-9=4). He had a narrow lifetime plus score of

+14-13=8.

Chigorin started serious chess rather late in life, and his

first international tournament

was Berlin 1881, where he was 3rd=.

He came second, ahead of reigning world champion Lasker and

former world champion Steinitz, in the Hastings 1895 chess

tournament, in which all the greatest players of the time

participated. The winner, Harry Nelson Pillsbury, lost their

individual game and had great respect for Chigorin's

ability. Chigorin maintained a narrow lifetime plus score

against him (+8-7=6).

He was 2nd= in Budapest 1896, and beat Rudolf Charousek +3-1

in the playoff. He was skilled at gambits, and won the

Vienna King's Gambit Tournament in 1903. He also beat Lasker

+2-1=3 in a sponsored Rice Gambit tournament in Brighton,

where he took black in every game; neither player took the

result as reflecting chess strength as opposed to the

weakness of the gambit.

Chigorin has several chess openings named after him, most

notably the Chigorin Variation of the Ruy Lopez (in

algebraic notation, 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6

5.O-O Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 d6 8.c3 O-O 9.h3 Na5). There is

also the Chigorin Defense to the Queen's Gambit (1.d4 d5

2.c4 Nc6).

Although Chigorin had a heavily negative record against

Lasker (+1-8=4), he beat Lasker with the black pieces in

their first game at Hastings in 1895. It resulted in a

classic two knights v two bishops ending, where Lasker's

bishops were better but he underestimated Chigorin's

strategy.

Chigorin had the measure of Richard Teichmann (+8-3=1) but

couldn't handle David Janowski (+4-17=4).

A famous Chigorin's match played against Wilhelm Steinitz in

1892 is used as the base for the plot of The Squares of the

City, a 1978 science-fiction novel by John Brunner.

770 Chigorin games in

PGN.

Amos Burn

Amos Burn (1848 - 1925) was one

of the world's top ten players

at the end of the 19th century.

Born in Hull, he learned chess

aged 16, came to London at the

age of 21, and rapidly

established himself as a leading

English player. He was a member

of the

Liverpool

Chess

club from 1867 until his death,

serving as its president for

many years. For a time he also

lived in

Hoylake, Wirral.

|

|

|

|

|

A pupil of Steinitz, he

developed a similar style; both

he and his master were among the

world's best six defensive

players, according to

Nimzovitsch. Not wishing to

become yet another impoverished

professional, Burn decided to

put his work (first a cotton

broker then a sugar broker)

before his chess, and he

remained an amateur. He made

several long visits to America,

and was often out of practice

when he played serious chess.

Until his thirty-eighth year he

played infrequently and only in

national events, always taking

first or second prize. From 1886

to 1889 he played more often. In

1886 he drew matches with Bird

(+9 -9) and Mackenzie (+4=2-4);

at London 1887 he achieved his

best tournament result up to

this time, first prize (+8- 1)

equal with Gunsberg (a play-off

was drawn + 1 =3- 1); and at

Breslau 1889 he took second

place after Tarrasch ahead of

Gunsberg. After an isolated

appearance at Hastings 1895 he

entered another spell of chess

activity, 1897-1901. The best

achievement of his career was at

Cologne 1898, first prize (+ 9 =

5 - 1) ahead of Charousek,

Chigorin, Steinitz, Schlechter,

and Janowski. At Munich 1900 he

came fourth (+9=3-3). His last

seven international tournaments

began with Ostend 1905 and ended

with Breslau 1912.

A comparative success, in view

of his age, was his fourth prize

shared with Bernstein and

Teichmann after Schlechter,

Maroczy, and Rubinstein at

Ostend 1906; 36 players competed

in this five-stage event, 30

games in all for those who

completed the course. Retired

from both business and play he

made his home in London and

edited the chess column of The

Field from 1913 until his death.

A shy and retiring man, a loyal

companion to those who came to

know him, he freely gave advice

to young and aspiring players.

Burn had a plus record against Alekhine,

beating him in Karlsbad 1911. Burn is the

eponym of the Burn Variation of the French

Defence (1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Bg5

dxe4). He was not the first to play the line

(according to Forster's biography, he first

adopted it against Charles D. Locock at

Bradford 1888, which postdates

Anderssen-Clerc, Paris 1878, for example),

but he was the first prominent player to do

so with any frequency.

Read more about Burn and others

at the

Museum of Liverpool Life

411 Burn games in

PGN

Joseph

Henry Blackburne

Joseph Henry Blackburne

(1841–1924), nicknamed "Black

Death", dominated the British

chess world during the latter

part

of

the 19th century. He learnt the

game at the relatively late age

of 18 but quickly went on to

develop a chess career that

spanned over 50 years. At one

point he was number two in the

world with a string of

tournament victories behind him

but he really enjoyed

popularising chess by giving

simultaneous and blindfold

displays around the country.

Blackburne

was born in Manchester in December of 1841. He first learnt

how to play draughts as a child and it wasn't until he heard

about Paul Morphy's exploits around Europe that he switched

to playing chess. He joined the Manchester Chess Club around

1860 and learned a lot about endgame theory from Bernhard

Horwitz, who had been appointed the resident chess

professional in 1857.

For the

next 20 years Blackburne toured the globe playing the greats

of world chess. He was regularly in the top 5 of the world

rankings and performed well in many international

tournaments. He was 1st= with Wilhelm Steinitz in Vienna,

1873, although he lost the playoff (-2); 1st in London,

1876; 1st with Berthold Englisch and Adolf Schwarz in

Wiesbaden, 1880; 1st in Berlin, 1881, where he finished 3

points ahead of his great rival Johannes Zukertort; 1st=

with James Mason in Belfast, 1892 and 1st at the London

tournament of 1893.

His results were decidedly mixed when he turned his talents

to matchplay though and he found it tough going against the

very best in the world. He lost two matches to Steinitz in

1862 (+1, -7, =2) and 1876 (+0, -7, =0) and lost a match to

Emanuel Lasker in 1892 (+0, -6, =4). He did better against

Zukertort; after losing a first match in 1881 (+2, -7, =5)

he managed to win the second in 1887 (+5, -1, =7) and he

performed similarly against Isidor Gunsberg in the same

years - winning in 1881 (+7, -4, =3) but losing the return

in 1887 (+2, -5, =6).

The 1876 match against Wilhelm Steinitz was held at the

West-end Chess Club in London and it was considered at the

time to be an unofficial world championship match. The

stakes were £60 a side with the winner taking all. This was

a considerable sum of money in Victorian times - £60 in

those days would be roughly equivalent to £4,000 in today's

money.

Blackburne made most of his money from touring the country

giving simultaneous exhibitions and blindfold displays.

Indeed he even visited the North-east of England in 1889 to

help promote the newly formed Teesside Chess Association.

Blackburne visited the area for two simultaneous displays

and a blindfold event. He charged 1/- for a simultaneous

game or 2/6d to play him blindfold and he proved to be

virtually unbeatable, winning 29, drawing 2 and losing only

one of the simultaneous games. In the blindfold he won 7 and

drew 1 with 0 losses.

His fondness for drinking whisky at the board once led him

to down an opponent's glass. Shortly afterwards, the

opponent resigned, leading him to quip, "My opponent left a

glass of whisky en prise and I took it en passant".

Blackburne held that drinking whisky cleared his brain and

improved his chessplay, and he tried to prove this theory as

often as possible.

The dubious chess opening the Blackburne Shilling Gambit

(1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Nd4?!) has been named for

Blackburne because he purportedly used it to win quickly

against amateurs, thus winning the shilling wagered on the

game. This has been questioned by Bill Wall, who says that

the phrase seems to have originated in the second (1992)

edition of Hooper and Whyld's The Oxford Companion to Chess,

and that there is no record of any games Blackburne played

with this opening.

By the 1890s Blackburne

was reputedly playing over 2,000 games a year in simuls and

he had even travelled abroad to countries like the

Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand to give exhibitions.

However he still had time to marry twice and with his second

wife, Mary Fox, he had a son. In addition he played top

board for the British team in 11 of the Anglo-American cable

matches which commenced in 1896 and in the first six matches

he recorded a score of 3½-2½ against the top American, Harry

Pillsbury.

In 1914 he tied for the British Championship with F.D. Yates

but at the age of 72 his best days were behind him and ill

health prevented him from contesting the play-off for the

title. Earlier in the same year he had competed in his last

major international tournament in St Petersburg, where he

beat the up-and-coming Aaron Nimzowitsch, but by now he was

concentrating on writing his chess column for The Field, a

position he held up until his death in 1924 at the age of

82.

Joseph Henry Blackburne is an icon of Romantic chess because

of his wide open and highly tactical style of play. His

large black beard together with his aggressive attacking

style earned him the nickname of 'der Schwarze Tod' (the

Black Death, referencing the plague of the same name) after

his performance in the 1873 Vienna tournament. In 1881,

according to one retroactive rating calculation (see

www.chessmetrics.com),

he was the second highest-ranked player in the world. He was

especially strong at endgames and had a great combinative

ability which enabled him to win many brilliancy prizes but

he will be best remembered for his popular simultaneous and

lightning displays which captured the imagination of the

general public who flocked to watch him.

871 Blackburne games

in PGN

Paul

Morphy

Paul

Charles Morphy (June 22, 1837 - July 10, 1884), "The Pride

and Sorrow of Chess," was an American chess player. He is

considered to have been the greatest chess master of

his time,

and was unofficial World Chess Champion.

Morphy was born in New Orleans,

Louisiana to a wealthy and

distinguished family. His

father, Alonzo Michael Morphy,

was a lawyer, state

legislator, state attorney

general, and state Supreme Court

Justice of Louisiana. Alonzo was

of Portuguese, Irish, and

Spanish ancestry. Morphy's

mother, Louise Therese Felicite

Thelcide Le Carpentier, was the

musically talented daughter of a

prominent French Creole family.

Morphy grew up in an atmosphere

of genteel civility and culture

where chess and music were the

typical highlights of a Sunday

home gathering.

In 1850, the strong professional Hungarian chess master

Johann Löwenthal visited New Orleans, and could do no better

than the amateur General Scott could. Morphy was 12 when he

encountered Löwenthal. Löwenthal, who had played young

talented players before and expected to easily overcome

Morphy, considered the informal match a waste of time but

accepted the

offer as a courtesy to the well-to-do Judge. When Löwenthal

met him, he patted him on the head in a patronizing manner.

He expected no more from Morphy than the usual talented

young players he had played before.

After 1850, Morphy did not play much chess for a long time.

Studying diligently, he graduated from Spring Hill College

in Mobile, Alabama in 1854. He then stayed on an extra year,

studying mathematics and philosophy. He was awarded a degree

with the highest honours.

Seeking new opponents and now aware that Staunton had no

real desire to play, Morphy then crossed the English Channel

and visited France. There he went to the Café de la Regence

in Paris, which was the centre of chess in France. He played

a match against Daniel Harrwitz, the resident chess

professional, and soundly defeated him.

In Paris he suffered from a bout of intestinal influenza and

came down with a high fever. Despite his illness Morphy

insisted on going ahead with a match against the visiting

German champion Adolf Anderssen and triumphed easily,

winning seven while losing two, with two draws in 1858. When

asked about his defeat, Anderssen claimed to be out of

practice, but also admitted that Morphy was in any event the

stronger player and that he was fairly beaten. Anderssen

also attested that in his opinion, Morphy was the strongest

player ever to play the game, even stronger than the famous

French champion Bourdonnais.

It was while he was in Paris in 1858 that Morphy played a

well-known game at the Italian Opera House in Paris, against

the Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard.

Shortly after, Morphy started the long trip home, taking a

ship back to New York. At the University of the City of New

York, on May 29, 1859,

John Van Buren, son of President Van Buren, ended a

testimonial presentation by proclaiming, "Paul Morphy, Chess

Champion of the World".

Morphy reportedly declared that he would play no more

matches with anyone unless he was giving odds of pawn and

move. After returning to his home, he declared himself

retired from the game, and with a few exceptions, he gave up

the public playing of the game for good.

Morphy's final years were tragic. Depressed, he spent his

last years wandering around the French Quarter of New

Orleans, talking to people no one else could see, and having

feelings of persecution. He was found dead in his bath on

the afternoon of July 10, 1884 by his mother. The doctor

said he had suffered congestion of the brain (stroke),

brought on by entering cold water after being very warm from

his long mid-day walk. He died at the age of only

forty-seven.

353 Morphy games

in

PGN.

Wilhelm Steinitz

Wilhelm

(later William) Steinitz (May 17, 1836, Prague - August 12,

1900, New York) was an Austrian-American chess player and

the first official world chess champion. Known

for his original contributions to chess strategy such as his

ideas on positional play, his theories were held in high

regard by such disparate chess players as Aron Nimzowitsch,

Siegbert Tarrasch, and Emanuel Lasker.

Born in Prague (today Czech

Republic, then Austrian Empire),

Steinitz was regarded the best

player in the world ever since

his victory over Adolf Anderssen

in their 1866 match. His 1886

match victory over Johannes

Zuckertort is considered by most

as the first World Chess

Championship.

Steinitz

defended his title from 1886 to 1894, retaining it in four

matches against Zuckertort, Mikhail Chigorin (two times) and

Isidor Gunsberg. He lost two matches against Lasker, in 1894

and 1896, who became his successor as world champion.

Steinitz adopted a scientific approach to his study of the

game. He would formulate his theories in scientific terms

and "laws".

After

losing the world title, Steinitz developed severe mental

health problems and spent his last years in a number of

institutions in New York, making a series of increasingly

bizarre claims (including his having won - at pawn odds!—a

game of chess with God conducted via an invisible telephone

line). His chess activities had not yielded any great

financial rewards, and he died a pauper in his adopted home

city in 1900. Steinitz is buried in Cemetery of the

Evergreens in Brooklyn, New York.

Emanuel

Lasker, who took the championship from Steinitz, once said,

"I who defeated Steinitz shall do justice to his theories,

and I shall avenge the wrongs he suffered." Steinitz's fate,

and Lasker's keenness to avoid a similar situation of

financial ruin, have been cited among the reasons Lasker

fought so hard to keep the world championship title.

Steinitz

began to play professional chess at the age of 26 in

England. His play at this time was no different than that of

his contemporaries: sharp, aggressive, and full of

sacrificial play. In 1873 however, his play suddenly

changed. He gave immense concern to what we now call the

positional elements in chess: pawn structure, space,

outposts for knights, etc. Slowly he perfected his new

method of play that helped form him into the first Chess

World Champion.

What

Steinitz gave to chess could be compared to what Newton gave

to Physics: he made it a true science. By isolating a number

of positional features on the board, Steinitz came to

realize that all brilliant attacks resulted from a weakness

in the opponent's defence. By studying and developing the

ideas of these positional features, he perfected a new art

of defence that sharply elevated the current level of play.

Furthermore, he outlined the idea of an attack in chess

formed off of what we now know as "Accumulation Theory", the

slow addition of many small advantages.

Though it was not immediately evident, Steinitz had just

given the chess world its greatest gift. Though tactics

were, and still are, the most basic element to strong play,

his new theory gave greater opportunity to both defend and

use the brilliant combinations the era was renowned for.

When he fought for the first World Championship in 1886

against Johann Hermann Zukertort, it became evident that

Steinitz was playing on another level. Though he suffered a

series of defeats at the beginning of the match, it becomes

evident when watching the games who understood the game

better (for example, in the third game he was strategically

superior but failed to pull it together at the end). Over

time however, Steinitz's level of play continued to improve

and finished with a solid victory (+10 -5 =5).

Perhaps the evaluation of Steinitz's impact on chess can

best be evaluated by a fellow master of strategy, Tigran

Petrosian: "The significance of Steinitz's teaching is that

he showed that in principle chess has a strictly defined,

logical nature."

694 Steinitz games in

PGN.

Howard Staunton

Howard Staunton (April

1810 - June 22, 1874) was a chess master and unofficial World Chess

Champion. He was also a newspaper chess columnist, chess book author,

and minor

Shakespearean scholar. His name is remembered most today for the style

of chess figures he endorsed, the "Staunton" pattern.

Little is known about the life

of Staunton before his

appearance on the chess scene.

He said he was born in

Westmorland and his father's

name was William. He was poor

and had no official

education when he was young. It

is known that in 1836, Staunton

was in London, and he made a

subscription to William Walker's

book Games at Chess, actually

played in London, by the late

Alexander McDonnell Esq.

From the age of 26 or so, he began a serious pursuit of the

game. In 1838 he played many games with Captain William

Evans, inventor of the Evans Gambit. He also played a match

against the German chess writer Aaron Alexandre and lost.

In 1840 he began writing, doing a chess column for the New

Court Gazette from May to the end of the year. He had

improved sufficiently by 1840 to play and win a match with

the German master Popert, which he won by a single game. He

also began writing for British Miscellany which in 1841 led

to his founding the chess magazine known as the Chess

Player's Chronicle. Staunton edited the magazine until 1854,

when he was succeeded by Robert Barnett Brien.

In 1842 he played hundreds of games with John Cochrane.

Cochrane was a strong player, and Staunton had a good

warm-up for what was to be his greatest chess achievement

the following year. In 1843, Staunton played a short match

with France's champion, Pierre St. Amant, who was visiting

London. Staunton lost the match, 3½-2½, but later

arrangements where made for a second match, to be held in

Paris. Staunton went to Paris, where from November 14 to

December 20, 1843, he played a match at the Cafe de la

Regence against St. Amant, beating him decisively, 13-8.

After St. Amant's defeat, no other Frenchmen arose to

continue the tradition of French chess supremacy started

with Philidor, and London became the chess capital of the